From the Irish Independent, 11 June 1914:

A grainier version of the above photo appears in the Freeman’s Journal of the same day, where the new barristers above are identified as Frederick Jerome Dempsey, Edward James Smyth, Samuel Spedding John, Thomas William Gillilan Johnson Hughes, Denis Bernard Kelly, Oliver L Moriarty, John Maher Loughnan, Isaac Roundtree, Ion George Wakely, Bernard Joshua Fox, John Henry de Burgh Shaw, Frederick William Callaghan, John McMahon, Edward Patrick McCarron, James Arthur Hill Waters, Walter Oakman Hume, Martin Arthur Lillie, Andrew Picken, Joseph Alphonsus Reddy and Henry Jerome Carvill.

Let’s take their subsequent life stories in the order in which their names appear above.

Frederick Jerome Dempsey was the second son of gynaecologist Sir Alexander Dempsey MD, Belfast. Fred practised as a barrister in Belfast for a few years before qualifying as a doctor in 1925. He died following a chill in 1938 at the the young age of 43. At the time of his death, he was assistant inspecting medical officer at the Children’s Clinic, Belfast. Kevin R O’Sheil BL, in a statement given by him to the Bureau of Military History, describes Dempsey as a nationalist in politics, and, through his father, a distinguished doctor, a steadfast supporter of the official Irish Parliamentary Party, though he held independent views and was highly critical of that party.

Edward James Smyth became President of the Castleknock College Union in 1937. It is unclear whether he worked as a barrister, a civil servant or both. In 1932 he was appointed to chair a public inquiry into the removal of foreshore from Greystones harbour. He died in 1941.

Samuel Spedding John joined the 9th Battalion Cheshire Regiment in Autumn 1914, after the outbreak of the First World War. In November 1915 he was awarded the Military Cross for conspicuous gallantry during fighting the previous September. After a retirement to the trenches had been ordered, Second Lieutenant John crawled out under heavy fire and assisted to bring in, in succession, a wounded officer and about twenty men of another regiment, thus saving many lives. According to the Wicklow Newsletter (Lt. John was from Bray) this was not the first time he had shown conspicuous bravery The report in the Newsletter included a letter from Lt. John’s sergeant to his family saying that if he asked of his men for their right hand they would give it and that they would follow him to certain death if needs be. Fortunately this did not become necessary as Lt. John survived the war, again being mentioned in despatches in 1915 and 1919 for gallant and distinguished service. He retired as an acting captain and appears to have subsequently become a judge in Cyprus.

Thomas William Gillilan Johnson Hughes, from a wealthy landowning family in Craigavad, County Down, enlisted in the Dublin Fusiliers in 1915 and subsequently served in the North Irish Horse, where he was mentioned in dispatches by Field Marshal Earl Haig and ended the war as a major. In 1939, Major Hughes featured as defendant in a road negligence case when two of his hunting horses collided with a car; damages of £5.17s were awarded against him.

Denis Bernard Kelly, from Killarney, went on to practice on the Munster Circuit for a number of years. He went on to become a District Justice. He died in 1969.

Oliver Moriarty, son of David Moriarty, Clerk of Crown and Peace for Kerry, served with the 2nd Munster Regiment during the War when he was seriously wounded by explosives at the battle of Loos. In April 1919 he was appointed Judge under the Egyptian Government in Cairo. He returned to Ireland in 1927 and resumed practice. The newspapers contain many reports of cases in which he was involved and he also appeared in two cases reported in the Irish Jurist Reports, one of them being a matrimonial case with Averil Deverell BL as opposing Junior. When he took silk in 1940, Mr Moriarty had the pleasant experience of being, in the one day, congratulated in three different courts by three different High Court judges, Mr Justice Hanna, Mr Justice Gavan Duffy and Mr Justice Black. He continued to maintain his busy practice as a Senior Counsel. Mr Moriarty died in 1953.

John Maher Loughnan had extensive previous experience in the hospitality industry, having taken over the Royal Victoria Hotel, Killarney, after the death of his aunt in 1903. By 1914, he had turned it into one of the most modern hotels in Ireland with a residents’ lounge, internal telephone and electricity. During this period he also visited a number of American cities to promote Killarney and Kerry as tourist destinations. He also served as chairperson of Killarney UDC. Unfortunately, the business did not flourish during the war and in 1920 he and his family were evicted by secured creditors. He went on enjoy a flourishing practice as an estate agent in Cork. Mr Maher Loughnan’s portrait was presented to Killarney UDC by his family in 2003.

Isaac Roundtree was a former auditor of the Trinity College Historical Society who briefly practised as a barrister before deciding to devote himself entirely to farming. In the 1920s he sued the head of a cattle owners’ association for assault committed on him due to his refusal to participate in the loading of cattle during the Dublin Dockers’ strike. His obituary in 1959 described him as a very successful farmer and a very good and charitable man who did good by stealth. It also expressed the view that had Mr Roundtree not opted for the call of the land over the call of the law he would almost certainly have had a very successful legal career in view of his outstanding academic achievements.

Ion George Wakely, was the son of solicitor William George Wakely, who acted as Secretary of the Incorporated Law Society for over 50 years between 1888 and 1943. He served as Captain in the Royal Garrison Artillery during the war, suffering facial disfigurement and lumbago as a result. He was also awarded the Military Cross. Captain Wakely subsequently became a Resident Magistrate in Jamaica before being tragically killed in a motor accident in 1943, the same year as his father’s death.

John Henry de Burgh Shaw served as a tank commander in the First World War before being appointed a District Commissioner in Sierra Leone in 1921. His father John Shaw of Cloncallow House, Co Longford, had previously been acting governor of Lagos.

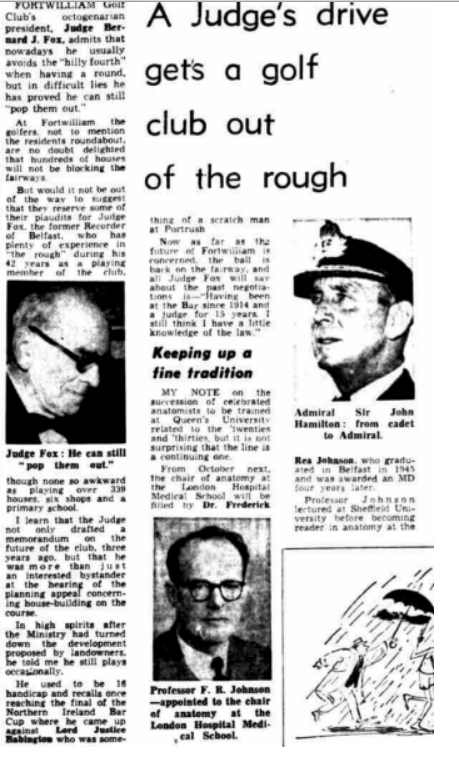

Bernard J Fox, a former auditor of the Law Students’ Debating Society, achieved top marks in his final Bar exam after winning many medals for oratory. One of his early cases was a matrimonial assault claim in which he defended a soldier suffering from shellshock. Like Walter Oakman Hume (below) Mr Fox opted to join the Northern Irish Bar and subsequently became a KC and Recorder of Belfast. His final appearance in the news was in 1968 when, as the octogenarian president of Fortwilliam Golf Club, he assisted the club in defeating an application for a development of nearby land which, had it gone through, would have resulted in 338 houses, six shops and a primary school, thereby inevitably stymieing the club’s activities. In an interview with the Belfast Telegraph, 25 July 1968, Mr Fox, in high spirits, remarked that he still had some knowledge of the law and had had plenty of experience ‘in the rough’ during his 42 years as a paying member of the Club. The headline inevitably commended the former judge’s ‘drive.’

Frederick William Callaghan died in Bristol, England in 1942, after a long illness. His obituary describes him as a barrister but it is not clear whether he ever practised in either Ireland or England.

John McMahon was a clerk in the Land Commission when called to the Bar, subsequently being appointed Higher Executive Officer in 1921. In 1929, he brought a claim for compensation under Article 10 of the Anglo-Irish Treaty and the Civil Service (Transferred Officers) Act 1929. Born in the 1870s, he was somewhat older than the other barristers, who presented him with a solid silver cigarette case at a dinner in the Gresham Hotel the week of the call as a souvenir of their regard and gratitude for the many kindnesses received from him. One suspects he may have provided assistance with property law queries! Also present at the dinner were Richard Armstrong, the Under-Treasurer of the King’s Inns, its legal professors Anthony B Babington and Robert Megaw, and law examiners John M Whitaker and C Norman Keogh.

Edward Patrick McCarron was a Local Government auditor and subsequently became Secretary to the Department of Local Government and Public Health.

James Arthur Hill Waters founded the 8th South County Scout group now known as 3rd Dublin Stillorgan, one of the oldest scout groups in Ireland. He was a lieutenant and subsequently a major in the Royal Army Service Corps. He lived at Callary, Dundrum and lost a son, Samuel, in the Second World War. There are references to him as being a civil servant in the Taxing Office in the Four Courts, and also as being a KC. I am not sure which is correct. Perhaps it was possible for Taxing Officers to take silk? He was a well-known motorcyclist both before and after the First World War. Major Waters died in 1965.

Walter Oakman Hume, from a legal family, practised on the North East Circuit and subsequently became a member of the Northern Irish Bar, taking silk in 1933 before dying in 1939 at the young age of 48. His obituary described him as an authority on land law with an extraordinary knowledge of caselaw. He was also a talented golfer who survived to the last eight in the Irish Open of 1921.

Martin Arthur Lillis, the youngest son of the managing director of the Munster and Leinster Bank, joined the Royal Flying Corps and was killed in April 1917.

Andrew Picken became Secretary of Queen’s University Belfast. When he died in 1938, after a long illness, its flags were flown at half mast in his memory. A brilliant classics scholar and ardent cricketer, he also served as a despatch rider during the First World War.

Joseph Alphonsus Reddy practised at the Irish Bar and enjoyed an extensive practice in Dublin, but died suddenly in 1929.

Henry John Carvill served in the South Irish Horse during the War. He was living in Chelsea, London, in 1920, when he gave evidence for the prosecution in an attempted fraud case (Carvill did not fall for the fraud – the newspaper headline was ‘Barrister did not Bite’). In 1922, he was called to the Bar of England and Wales. He died in 1955.

Two Military Crosses, three colonial judges, one Northern Irish judge, one Irish District Justice, one Irish KC, two Northern Irish KCs, one wartime death, many, many early deaths! The barristers of 1914 were certainly an unlucky bunch from the start – what could be worse than a world war breaking out between your call and the start of your devilling year – but, given how young they all look in the above photograph, it’s shocking to think that more than half of them were already dead within thirty years of its being taken!

These are the very first group of Irish barristers to appear in the newspaper on their call. Did the barristers of 1915 live longer? Find out soon!